Contents |

See also |

||

Look here if your video player has troubles in playing the videos files.Check also the video page for our book with many videos (all with flash player). |

| See also Videos page of the paper! |

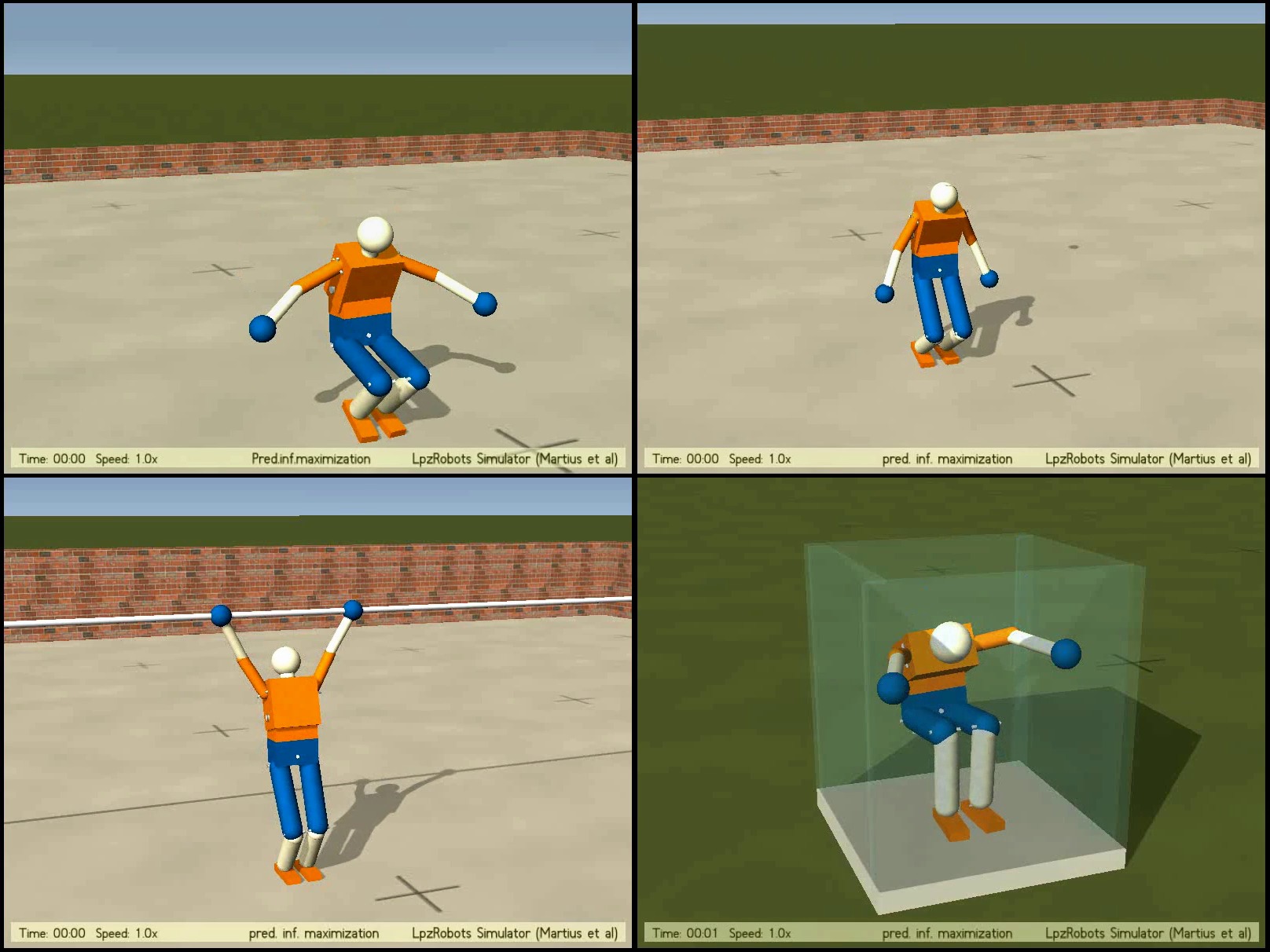

Predictive Information Maximization -- The Playful Machine II

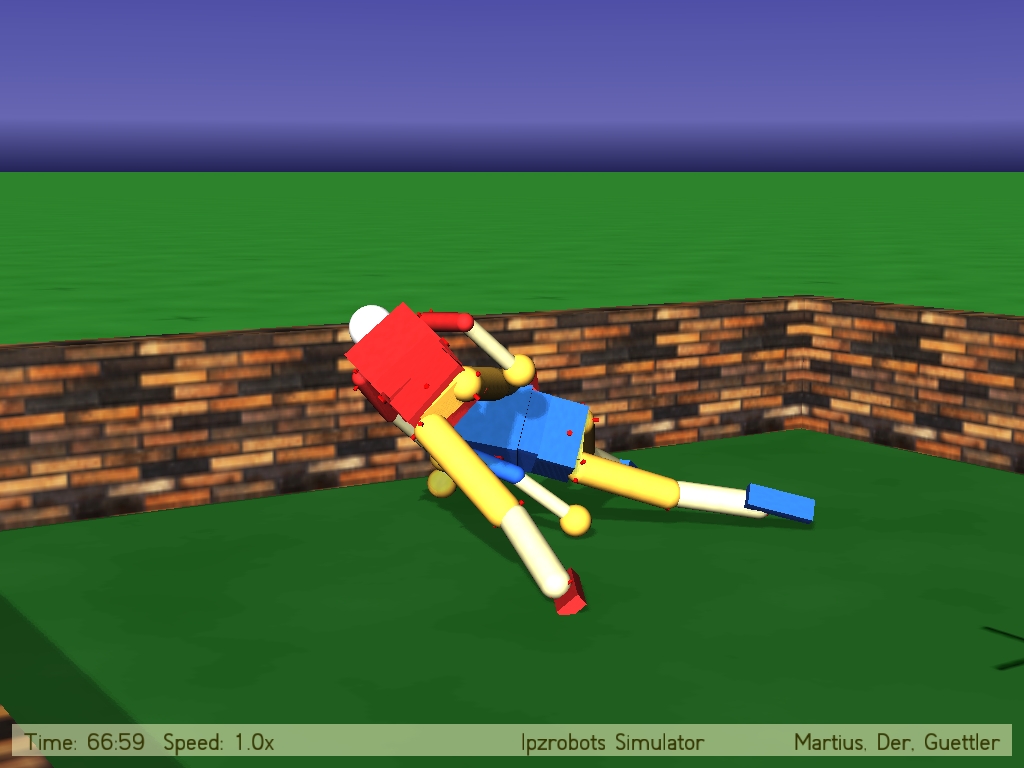

Information theory is a powerful tool to express principles to drive autonomous systems because it is domain invariant and allows for an intuitive interpretation. This paper studies the use of the predictive information (PI), also called excess entropy or effective measure complexity, of the sensorimotor process as a driving force to generate behavior. We study nonlinear and nonstationary systems and introduce the time-local predicting information (TiPI) which allows us to derive exact results together with explicit update rules for the parameters of the controller in the dynamical systems framework. In this way the information principle, formulated at the level of behavior, is translated to the dynamics of the synapses. We underpin our results with a number of case studies with high-dimensional robotic systems. We show the spontaneous cooperativity in a complex physical system with decentralized control. Moreover, a jointly controlled humanoid robot develops a high behavioral variety depending on its physics and the environment it is dynamically embedded into. The behavior can be decomposed into a succession of low-dimensional modes that increasingly explore the behavior space. This is a promising way to avoid the curse of dimensionality which hinders learning systems to scale well.

Humanoid

Humanoid in different environemnts MPEG4-H264 (15.1 MB) © Georg Martius |

See also Videos page of the paper! |

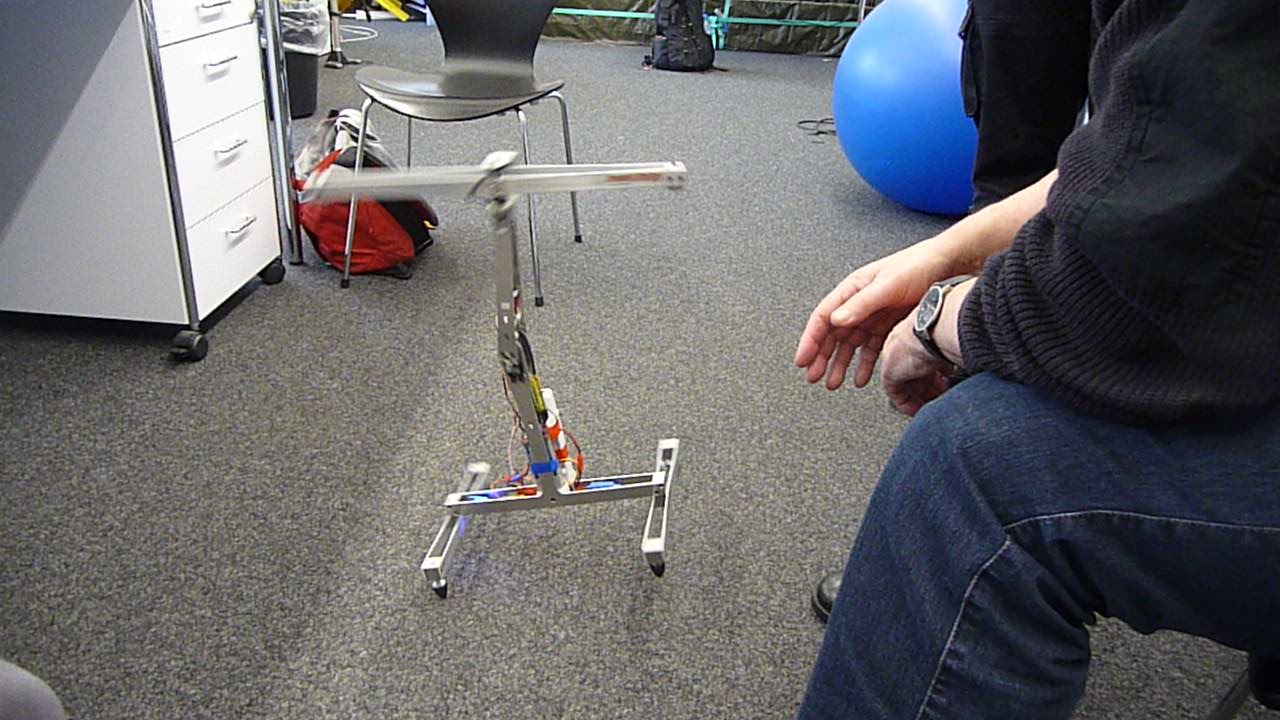

Stumpy

The robot was developed and built in Rolf Pfeifer's lab, Zürich. Thanks for giving us the change to try our algorithms.

Locomotion 1 DIVX4 (13.3 MB) © Georg Martius |

Locomotion 1 DIVX4 (12.4 MB) © Georg Martius |

Turning DIVX4 (27.2 MB) © Georg Martius |

See also Videos page of the paper! Here are some things we have observed just after connecting our algorithm. Note that the robot does not move when grasped because the acceleration sensors (are only sensor information) stay more or less constant. |

Homeokinesis -- The Playful Machine I

The homeokinetic objective is mainly to make the robot sensitive so that small variations in sensor values induce large variations in motor values resulting in even larger sensorial responses and so on. This would drive the robot towards a hyperactive, chaotic behavior. The way into complete chaos is counteracted by both the physics of the robot itself (inertia, cross relations, ...) and the decline of understanding in the chaotic regime. As a solution of these conflicting effects the robot develops a kind of self-exploration of its bodily affordances in a more or less playful way with a tendency to development due to increasing cognitive abilities.We present below a number of examples demonstrating that this principle, called also the principle of homeokinesis, can be translated into a reliable, extremely robust algorithm which governs the parameter dynamics of the neural networks for both the self-model and the controller. Videos are from simulated environments as well as from real world experiments.

Book

Many more details and theoretical results on found in our book The Playful Machine (now available online).View report by Daily Telegraph

Semni

The robot was developed and built by Manfred Hild, HU Berlin. We thank for the collaboration!

Compilation DIVX4 (10.8 MB) © Georg Martius |

With weight DIVX4 (9.2 MB) © Georg Martius |

We had one day to connect our controller to the robot and observe what happens. Note how sensitive the robot it its acceleration sensors when touched or moved externally. See also the video page for our book. |

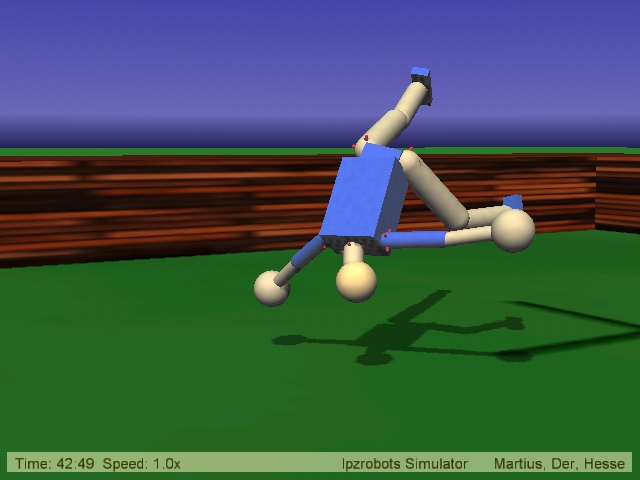

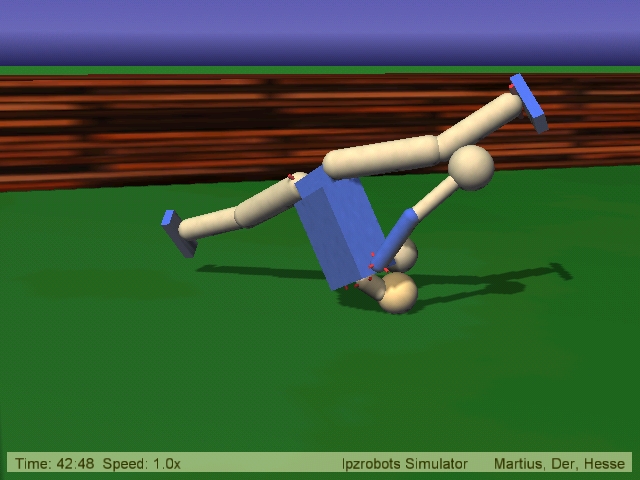

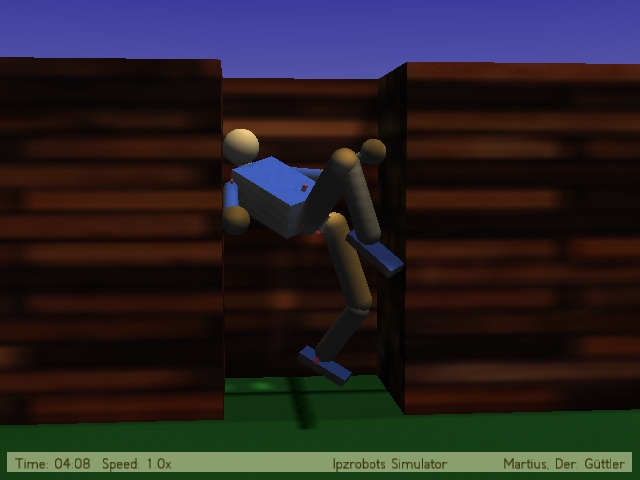

Humanoid robots

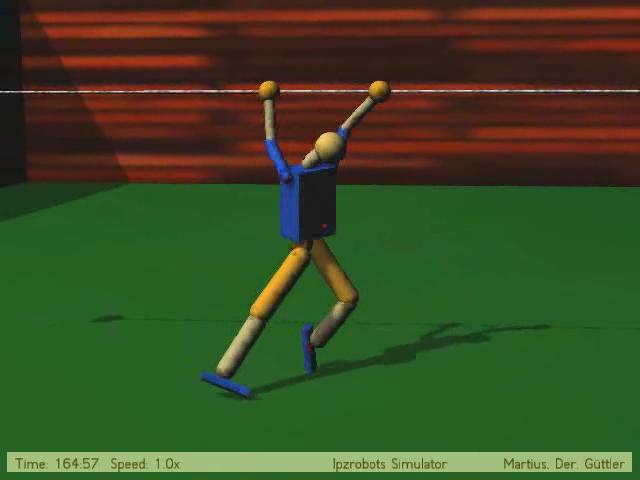

Please note that the gravity in these experiments is only half the earth value. This is what makes the motions a little slow-motion like.

Back Flip AVI (0.5 MB) (0.1 MB) DIVX4 (0.3 MB) © Ralf Der |

Rolling over AVI (0.6 MB) (0.1 MB) DIVX4 (0.4 MB) © Ralf Der |

In full action AVI (5.2 MB) (1.0 MB) DIVX4 (3.3 MB) © Ralf Der |

Motion patterns emerging in the course of time if the robot is left alone in free space. The robot is controlled by our self-regulating neural network according to the homeokinesis principle. The joints are actuated by simulated servomotors. Sensor values are the joint angles. There is no other information available to the robot. |

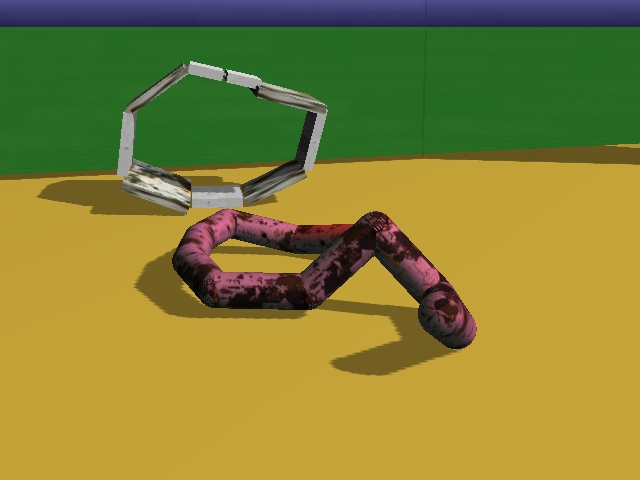

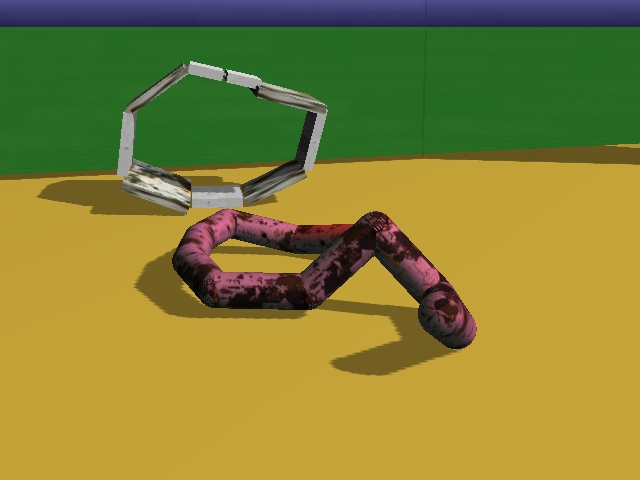

Robot Wrestling

Two humanoid robots in a kind of wrestling interaction. Sensor values are just the true angle of the joints. The robots can only "feel" each other by the mismatch between true (measured)and nominal joint angles resulting from the load on the joint. Adherence is due to normal friction but essentially also from a failure of the ODE physics engine, which after heavy collisions produces an unrealistic penetration effect which makes the collision partners adhere to each other. So, the "fighting" is actually a truely emerging phenomenon not expected before we saw it.

MPEG2 (124.2 MB) DIVX4 (5.9 MB) © Ralf Der |

DIVX4 (3.3 MB) © Ralf Der |

AVI (7.5 MB) (1.6 MB) DIVX4 (5.0 MB) © Ralf Der |

AVI (6.1 MB) (1.3 MB) DIVX4 (4.0 MB) © Ralf Der |

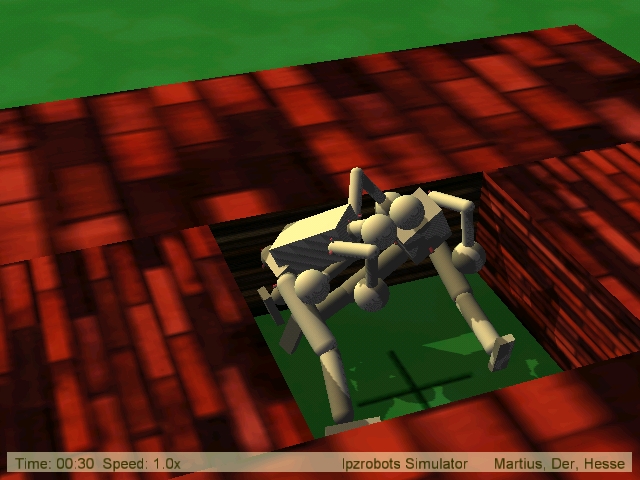

Self-rescue

A self-rescue scenario: AVI (1.7 MB) (0.3 MB) DIVX4 (1.0 MB) © Ralf Der |

The robot in a narrow pit develops after some time motion patterns which may help it to get out of the impasse.

|

Bar exercise

A bar excercise scene AVI (13.0 MB) (2.4 MB) DIVX4 (8.6 MB) (2.2 MB) © Ralf Der |

Two hours later AVI (5.0 MB) (0.9 MB) DIVX4 (3.2 MB) © Ralf Der |

=> back to top

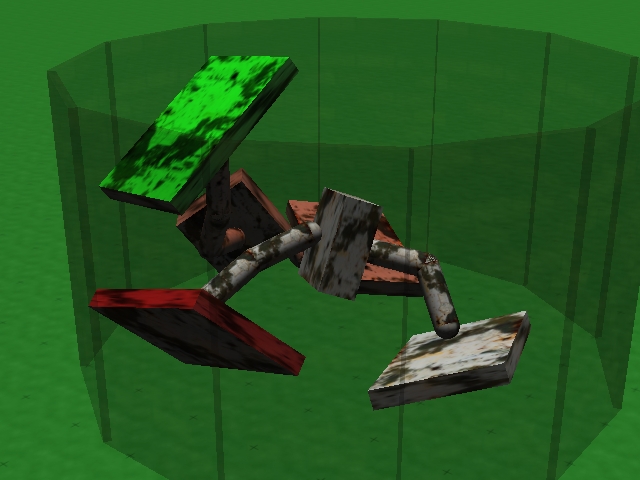

Dogs, Snakes & Co.

Our dog robot

Dog fixed in the air AVI (1.3 MB) (0.2 MB) MPEG2 (1.5 MB) DIVX4 (0.8 MB) © Georg Martius |

Dog fixed in the air II AVI (1.1 MB) (0.2 MB) MPEG2 (1.4 MB) DIVX4 (0.7 MB) © Georg Martius |

Dog surmounting a barrier 1 AVI (6.7 MB) (1.3 MB) DIVX4 (8.8 MB) © Ralf Der & Georg Martius |

Dog surmounting a barrier 2 AVI (8.0 MB) (1.4 MB) MPEG2 (10.7 MB) DIVX4 (5.4 MB) © Ralf Der & Georg Martius |

The hippodog AVI (7.6 MB) (1.5 MB) DIVX4 (10.0 MB) © Ralf Der & Georg Martius |

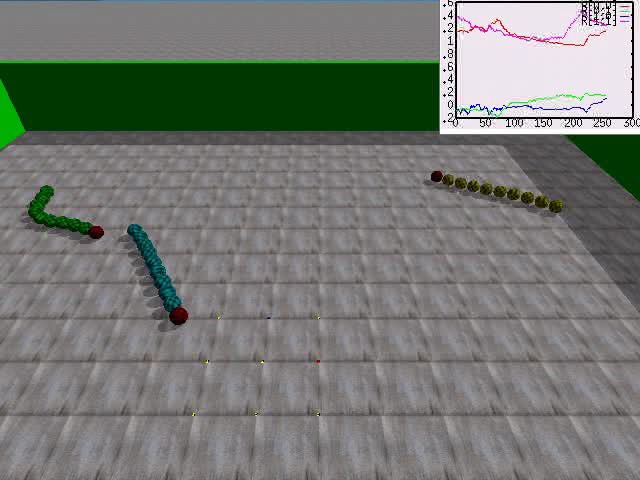

Snakes and other strange objects

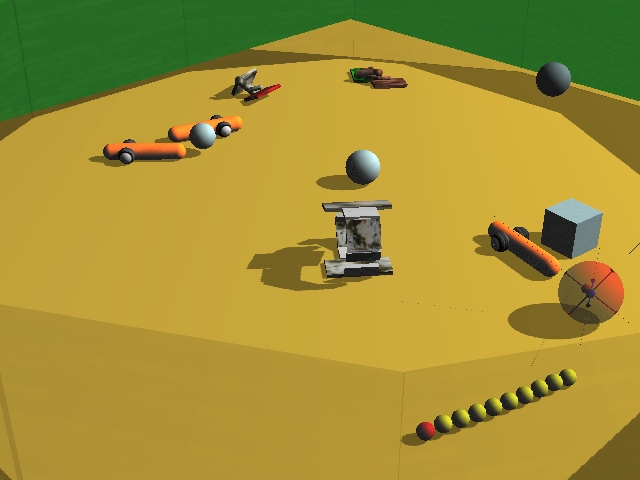

We are presently arranging our zoo anew. Here you may wish to find a first impression of some of the "creatures" who will "live" there. Each of the creatures is equipped by the same neural system (differing in the number of motor neurons and sensor inputs only)with a fast synaptic dynamics driven by our general paradigm of self-organization. Initialization of the synaptic values is such that the creatures are essentially in a "do nothing" and "know nothing" state.-

The snake in a narrow pit:

AVI (8.0 MB) (1.5 MB)

MPEG1 (15.0 MB)

DIVX4 (10.4 MB)

© Ralf Der

One of the surprising events: In the middle of the video the snake spontaneously tries to jump out of a very narrow pit (gravity half the earth value)

see also "Coiling Mode" and " a more lengthy video here" . - In "an escape" the snake is seen to jump out of the vessel. Please note that the gravity in the experiments is always that of the moon which explains the "slow motion" character of the scenes. (M1V-Format, 1,8 MB)

- In jump weight (M1V-Format, 1,9 MB) the snake jumps with a heavy weight.

- In "fat man nr. 1" a modification of the snakes seems to behave in a rather intricate way in order to escape from the vessel. (M1V-Format, 6,3 MB)

- In a later phase the "legs" are much better coordinated which essentially alters the character of the behavior. See the fat man nr.2 (M1V-Format, 14,7 MB)

- The flatfoot world:

AVI (9.9 MB) (1.8 MB)

MPEG1 (18.7 MB)

© Ralf Der

- Rolling wheelie-like robot:

Rolling Wheelie

AVI (3.2 MB) (0.7 MB)

MPEG2 (4.1 MB)

DIVX4 (2.1 MB)

© Georg Martius

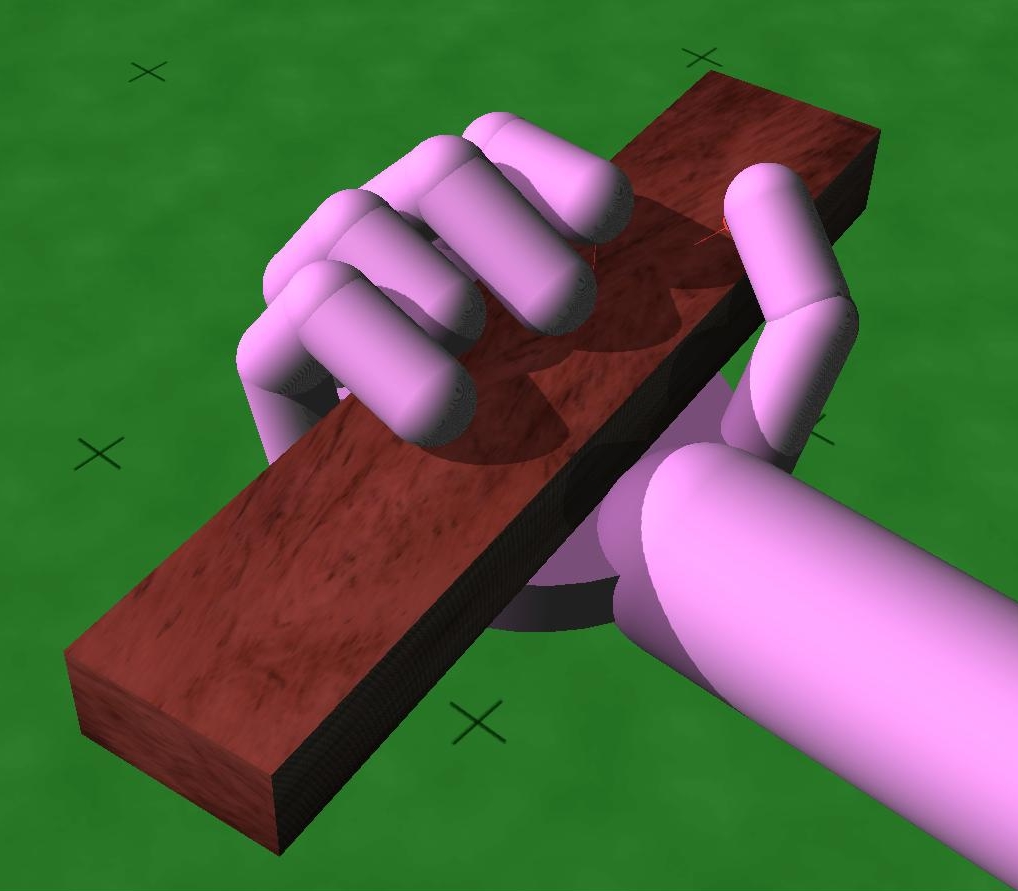

Human Hand Model

AVI (0.0 MB) (0.0 MB) MPEG2 (5.7 MB) © Ralf Der & Frank Hesse |

Simulation of a human hand with multiple degrees of freedom (in this simulation only 6 degrees of freedom are used). The hand is equipped with motion sensors at all joints. The infrared sensors at the finger tips are not used in this experiment. It is operated in a fully exploratory mode with or without a manipulated object. |

Information and complexity

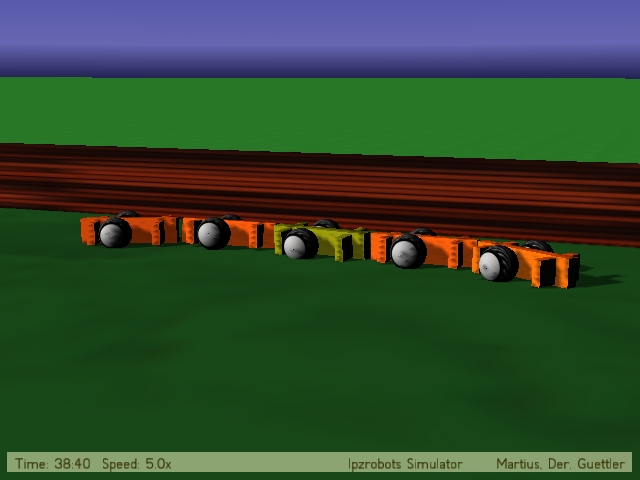

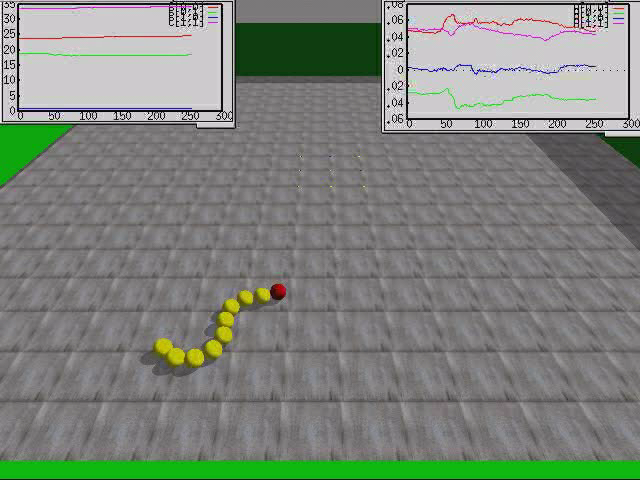

Measures of complexity are of immediate interest for the field of autonomous robots both as a means to classify the behavior and as an objective function for the self-organization and autonomous development of robot behavior. In a recent paper and in a presentation we consider predictive information in sensor space as a measure for the behavioral complexity of a chain of two-wheel robots which are passively coupled and controlled by a closed-loop reactive controller for each of the individual robots. The predictive information (approximated by the mutual information in the time step) of the sensor values of an individual robot is found to have a clear maximum for a controller which realizes the spontaneous cooperation of the robots so that the chain as a whole can develop an explorative behavior in the given environment. In the videos the robots are driven by a controller which sees the current wheel velocities x(i) as sensor inputs and produces motor values (nominal wheel velocities) y(i) asy(i) = tanh( C[i,1] x(1) + C[i,2] x(2))

where i = 1,2 is the wheel index. There are no other sensors like reporting collisions or measuring the coupling forces between robots. Each robot in the chain has a controller with the same set of parameters. The behavior of the robot chain depends in a very sensitive way on the parameters C[i,j] of the individual controller. Coarsely speaking, the parameters define a kind of geheralized feed back strength in the sensorimotor loop. If the feed back is around a critical value, the controllers react very sensitively to the perturbations, exerted by the other robots in the chain, on the wheel velocities, so that synchronization of wheel velocities becomes possible. In the videos below we present behaviors with different values of the predictive information both at and away from the maximum.

In order to unserstand the relation between the behavior and the predictive information (PI) we note, as a rule of thumb, that the PI is high if both the behavior is rich (high acitivity, exploring the space of sensor values) but not too chaotic or random so that the future sensor values (here in the next time step) ar still predictable to a certain degree at least.

Behavior in an arena without obstacles

| The subcritical behaviour: Low PI. Incoherent fluctuations. Low activity (narrow range of sensor values) and some predictability C[0,0]=C[1,1]=0.8 and C[0,1]=C[1,0]=0.0  AVI (2.0 MB) (0.4 MB) DIVX4 (1.3 MB) © Frank Güttler & Ralf Der |

Near optimal behaviour: High PI due to a good balance between activity (wide range of sensor values) and predictability. C[0,0]=C[1,1]=1.0 and C[0,1]=C[1,0]=0.07  DIVX4 (2.5 MB) © Frank Güttler & Ralf Der |

The supracritical behaviour: Low PI due to high activity but only switching of sensor values and reduced predictability System is caught in a behavioral mode. C[0,0]=C[1,1]=1.4 and C[0,1]=C[1,0]=0.0  DIVX4 (1.2 MB) © Frank Güttler & Ralf Der |

Behavior in a maze with obstacles

| The subcritical behaviour: C[0,0]=C[1,1]=0.8 and C[0,1]=C[1,0]=0.0  MJPEG (8.0 MB) DIVX4 (0.4 MB) (0.1 MB) © Frank Güttler & Ralf Der DIVX-Format (320x240, 0,3 MB) | The critical behaviour: C[0,0]=C[1,1]=1.0 and C[0,1]=C[1,0]=0.1  AVI (1.8 MB) (0.5 MB) DIVX4 (1.1 MB) (0.3 MB) © Frank Güttler & Ralf Der |

The supracritical behaviour: C[0,0]=C[1,1]=1.3 and C[0,1]=C[1,0]=0.2  AVI (2.5 MB) (0.6 MB) DIVX4 (1.6 MB) (0.4 MB) © Frank Güttler & Ralf Der |

Older videos on the role of predictive information in sensor space.

| Demo 1 AVI (3.0 MB) (0.6 MB) MPEG2 (3.8 MB) DIVX4 (1.9 MB) © Frank Güttler & Ralf Der |

Demo 2 AVI (3.0 MB) (0.6 MB) MPEG2 (3.8 MB) DIVX4 (1.9 MB) © Frank Güttler & Ralf Der |

Demo 3 AVI (2.7 MB) (0.5 MB) MPEG2 (3.5 MB) DIVX4 (1.8 MB) © Frank Güttler & Ralf Der |

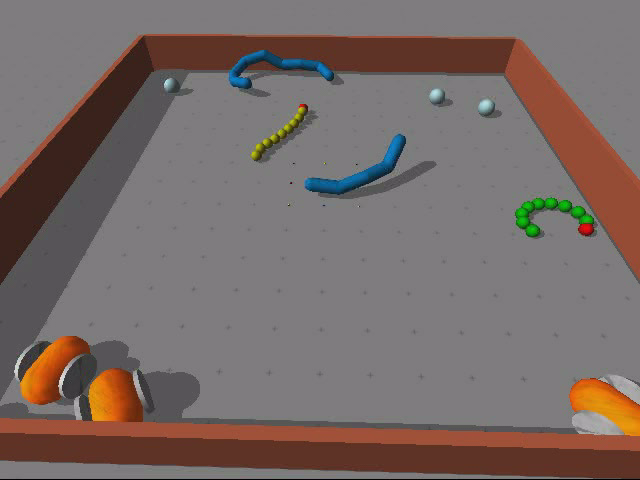

The zoo

The videos presented are sections of multiple one-hour runs of the zoo starting from a trial initialization of the parameters of both the controller and the world model. All creatures in the world have only proprioceptive sensors so that they have no notion of the positions of other agents or the obstacles. The differences being only in the number of controller neurons, the quality of sensors and similar technical details.Videos:

Life is starting in the zoo AVI (23.7 MB) MPEG2 (28.4 MB) © Georg Martius |

The zoo in full action AVI (12.6 MB) MPEG2 (13.1 MB) © Georg Martius |

The somewhat jerky run of the video streams originates from technical problems when recording it. The original computer simulation is free of these artefacts.

The new Zoo

AVI (3.8 MB) (0.8 MB) MPEG1 (7.0 MB) © Georg Martius |

AVI (7.0 MB) (1.6 MB) MPEG1 (13.0 MB) © def |

AVI (7.9 MB) (1.6 MB) MPEG1 (14.9 MB) DIVX4 (10.3 MB) © def |

We see that each of the agents develops a kind of behavior of its own which is emerging from the interplay of its body with the environment. Behaviors are largely modified by the interactions with the obstacles in the arena and with other agents. The latter kind of interactions makes our zoo a highly dynamic environment.

=> back to topFurther videos from virtual worlds

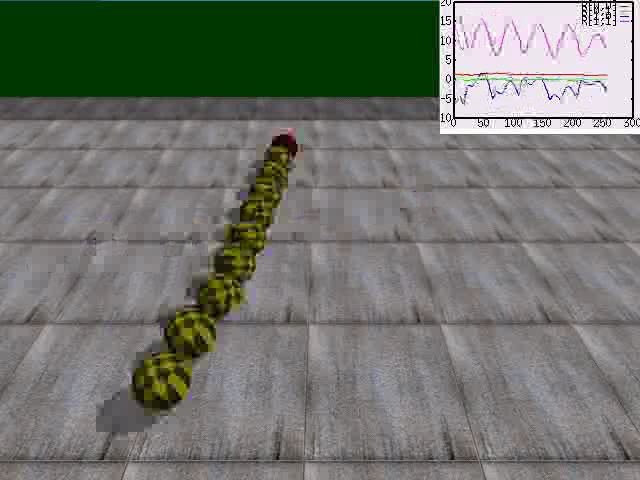

The skidding snake - How the "brain" learns to feel its body.

We consider a snake consisting of a string of spheres with an active head to which a force vector (lying in the plane) is applied. The force is controlled by our neural network (the "brain") which is self-regulating according to our general paradigm. The force is so weak that only rolling lateral motions are possible. As you can see after some time the "brain" develops a "feeling" for the swaying of the body so that it can drive the snake into a rotational mode. But also these modes are transients, i.e. they appear and decay repeatedly in the course of time. The apparent stiffness of the body results from gyro effects due to the induced rapid rotation by the spheres.Videos:

- Transition to the rotational modus with parameters

and

and  (world

model

and controller).

(world

model

and controller).

AVI (12.1 MB)

MPEG2 (13.3 MB)

© Frank Hesse

The parameters of the world model demonstrate how the model relearns in order to reflect the different reactions of the complex body (the string of gyros) to the applied forces. In the beginning the motions are very slow so that the response of the body is weak. This is reflected by the small values of the matrix elements of

. When the snake is transiting into the

rotational mode the parameters of both the controller and the world

model

drastically change, the latter reaching essentially a rotation matrix.

. When the snake is transiting into the

rotational mode the parameters of both the controller and the world

model

drastically change, the latter reaching essentially a rotation matrix. - Different rotation modes and robustness against

pertubations. (with parameter

)

)

AVI (9.2 MB)

MPEG2 (9.6 MB)

DIVX4 (6.7 MB)

© Frank Hesse

All three snakes are probing into different frequencies, which are seen to be transient.

- Frequency decreasing.

AVI (5.0 MB)

MPEG2 (5.3 MB)

© Frank Hesse

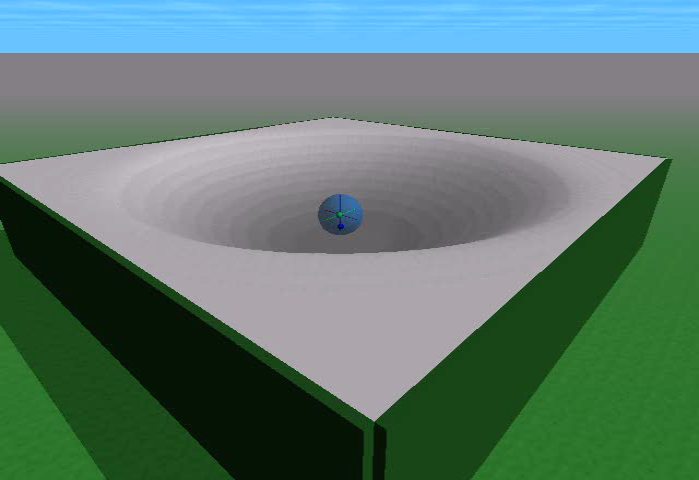

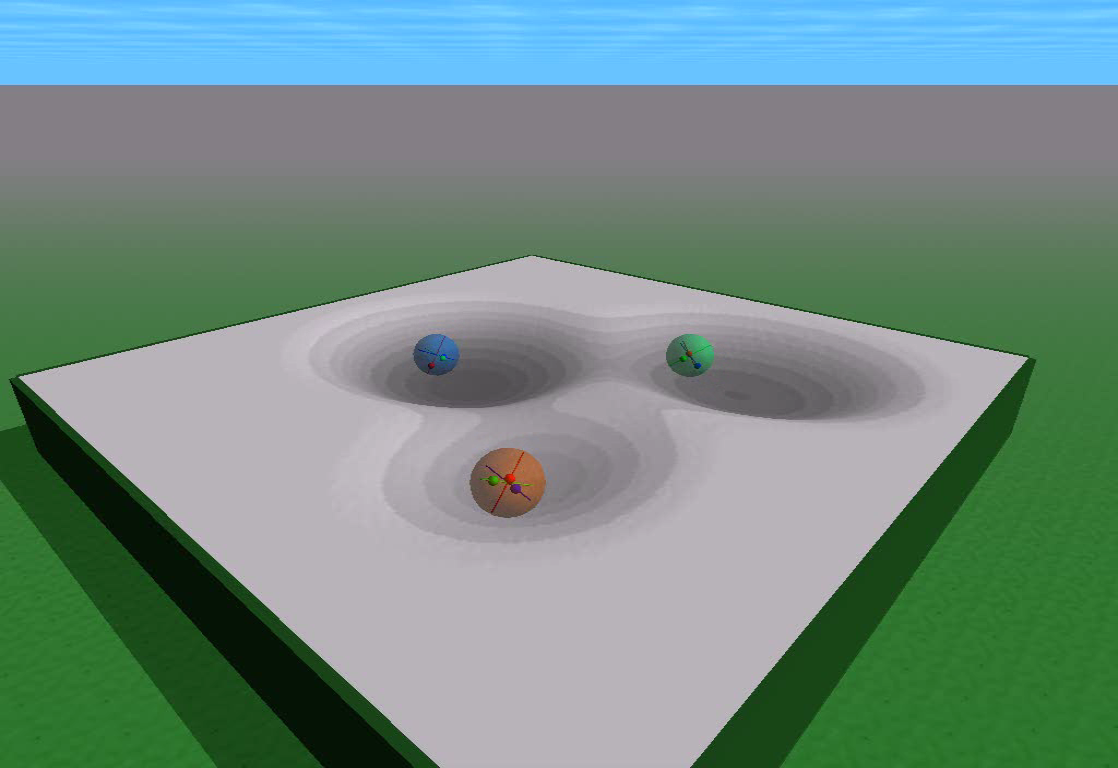

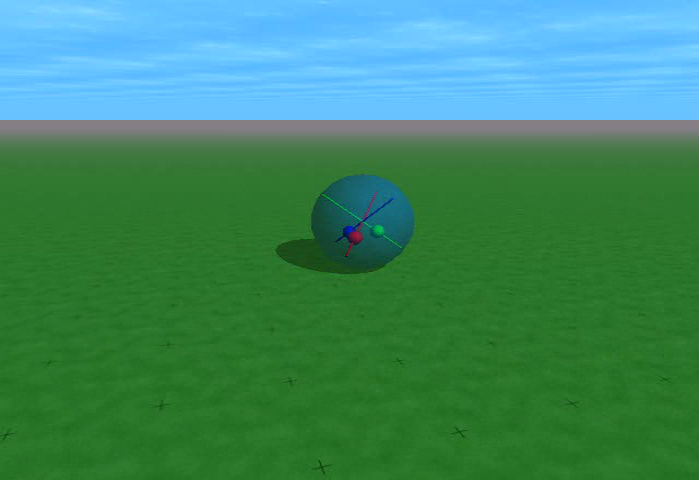

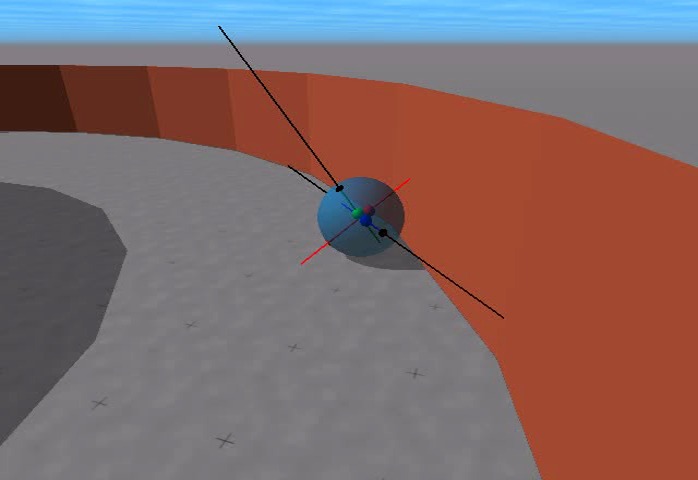

Spherical robots

Spherical robots are inspired by Julius Popp. Our robot is driven by 3 internal masses moving along three orthogonal axes running through the center of the sphere. We made the shell semi transparent in order to allow the observer to have a look inside. Sensor values are the projections of the internal axes on the z-axis of the world coordinate system. Motor values are the position of each of the masses on its axis. Both sensor and motor values are related to the motions of the sphere in a very complicated manner. Nevertheless in the experiments the spheres roll long distance, can stop and turn. In the basins of the landscape the spheres even roll circles at constant heights or escape. The behaviors manifest the emerging sensorimotor coordination.New Videos (2006):

- Two spherical robots in a landscape of three basins. This is a short video.

AVI (0.7 MB) (0.2 MB)

MPEG1 (1.3 MB)

© Georg Martius

- Two spherical robots in the landscape. Here is a longer video.

AVI (14.9 MB) (2.8 MB)

MPEG1 (28.2 MB)

© Georg Martius

Videos:

- One spherical robot in a basin.

SVGA resolution (1024x768)

AVI (15.0 MB) (2.8 MB)

MPEG2 (41.5 MB)

© Georg Martius

- Spherical robot in three overlapping basins similar to

the Robodrom by Julius Popp.

AVI (13.9 MB) (2.5 MB)

MPEG2 (41.2 MB)

© Georg Martius

- In the previous video one of the sphericals went off the

playground. It was followed by the camera to see what it does on the plane.

AVI (16.6 MB) (3.0 MB)

MPEG2 (48.9 MB)

DIVX4 (34.5 MB)

© Georg Martius

- We have equipped the spherical robot with infrared (IR)

sensors. In the simulation the sensors are visualized by rays. Black

color means maximal distance (no IR response) and red means lower

distance (high IR response). In the following Video you see it in a

corridor.

Paper: Let it roll -- Emerging Sensorimotor Coordination

in a Spherical Robot

AVI (15.6 MB) (2.9 MB)

MPEG2 (46.0 MB)

DIVX4 (20.5 MB)

© Georg Martius

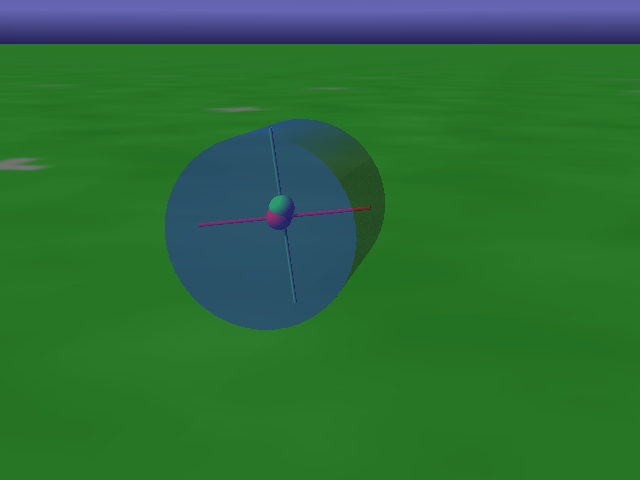

- One barrel-like robots on flat ground. This video shows how different speeds are used.

AVI (18.4 MB) (3.3 MB)

MPEG2 (24.1 MB)

DIVX4 (12.2 MB)

© Georg Martius

Cognitive Deprivation

Cognitive deprivation is a phanomena that occurs if the sensor-action space in only explored partially and a world model is learned online. Assuming some synaptic decay we will observe a restiction of the world model to the space actuated by the controller.Videos:

- 2 Wheeled robot with restricted Controller: In this movie the controller was fixed for the

first half of the movie. Only some bias was modulated, so that the robot is driving only

forward and backward.

The learning is enabled, which is indicated by a color change of the robot, and we see strong

exploration of the rotational behaviour space.

AVI (6.3 MB) (1.2 MB)

MPEG2 (8.0 MB)

DIVX4 (4.0 MB)

© Georg Martius

Swarms

Cigars are wheel-driven robots with long bodies. The videos show an arena with each wheeled cigar controlled by our algorithm individually. The wheel counters are the only sensors. The vehicles show an explorative but sensitive behavior and do not get stuck even in very long runs and in overcrowded arenas (as shown in the last video).Videos:

- AVI (15.1 MB)

MPEG2 (15.8 MB)

- AVI (15.6 MB)

MPEG2 (15.9 MB)

- AVI (15.4 MB)

MPEG2 (15.9 MB)

- AVI (19.7 MB)

MPEG2 (20.3 MB)

- AVI (7.1 MB)

MPEG2 (7.2 MB)

- with parameter evolution plot

AVI (19.6 MB)

MPEG2 (20.8 MB)

Experiments with real robots

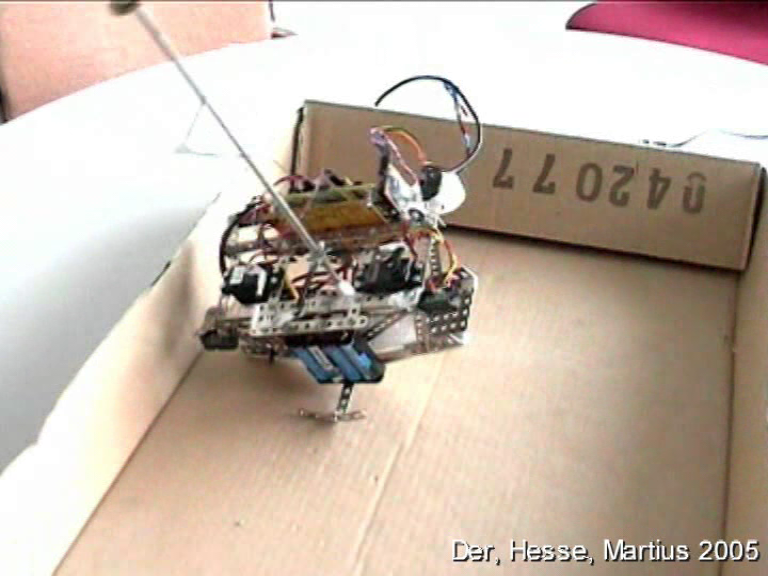

In the following you will find some examples of the application of the general principle to the self-organized behavior generation in real robots. We use the same controller as in the virtual world with the same learning algorithm. However we additionally have to account for delay effects which are not present in the virtual world.The rocking stamper

Our stamper consists of a trunk with a pole driven by two servomotors. Controller outputs are the angles of the pole relative to the trunk. The four infrared sensors are looking downward and are only coarsely related to the motions of the body. Nevertheless our algorithm is able to close the sensorimotor loop and produce oscillations leading to rocking or walk-like modes of behavior. So the sensorimotor coordination (manifested by the arising oscillations) is achieved on the basis of extremely unreliable information. Moreover the experiment with flapped/disabled sensors shows that the learning is able to integrate new sensors or to disintegrate defect sensors from the sensorimotor coordination in a very short time (less than a minute in the experiments).Videos:

|

Behavior 1

|

Behavior 2

|

Demonstration sensor control 1

|

Demonstration sensor control 2

|

Wheeled robot

In the Maze

Here and in the following videos the robot uses only its wheel sensors as inputs for the controller. Collissions are "felt" by the fact that the model of the sensorimotor loop is violated. Large model errors produce faster changes of behavior. In free space the model error is small so that the behavior persists over longer times.

AVI (1.8 MB) © Ralf Der & Rene Liebscher |

AVI (5.5 MB) © Ralf Der & Rene Liebscher |

AVI (1.6 MB) © Ralf Der & Rene Liebscher |

Playing ball

In addition to the wheel velocities the velocities of the ball in the camera plane are used as sensors. The algorithm forces the closing of the sensorimotor loop over the camera and so an explorative behavior with a ball playing mode is generated.

AVI (3.5 MB)

© Ralf Der & Rene Liebscher

=> back to top

Our general paradigm driving self-organization

In the videos you can see a number of different agents in an arena.

Each of

those is driven by a controller which is a neural network with a fast synaptic dynamics obtained from our general principle of

homeokinesis

realized as

gradient

descending an objective function ![]() which coarsely speaking is the weighted matrix

norm

which coarsely speaking is the weighted matrix

norm

where

This completely domain invariant principle is seen to generate

behaviors which

are different for each agent and which change over time. The zoo

may be run

forever with the behaviors changing over time. The different actors of

the

scene are presented in their details and specific properties in the

following

below. Here we want to demonstrate that the paradigm can be translated

into a

feasible, extremely robust algorithm despite of the mathematical

subtleties

involved with ![]() ,

cf. Eq. 1, like the fact that

it contains the

inverse of the Jacobian matrix. Moreover a more detailed analysis of

the

dynamics shows that the crucial point of the concomitant learning of

the world

model and the controller is solved by the algorithm in a reliable and

controlled way although the world is highly unstructured and dynamic.

,

cf. Eq. 1, like the fact that

it contains the

inverse of the Jacobian matrix. Moreover a more detailed analysis of

the

dynamics shows that the crucial point of the concomitant learning of

the world

model and the controller is solved by the algorithm in a reliable and

controlled way although the world is highly unstructured and dynamic.

Trouble shooting of video playback

Windows

The .avi videos (DivX Format) need an MPEG4-Codec installed on your system like Xvid or DivX. Unfortunately, not all versions of the Windows Media Player have this codec by default, please install them to watch the videos. There are three suggestions:

- The OpenSource K-Lite Codec Pack

- downloadable at http://www.codecguide.com/

- supports Windows NT/2000/XP/Vista 32/64bit

- The commercial Free DivX software

- downloadable at http://www.divx.com/

- supports Windows 2000/XP/Vista 32bit and Mac OS X

- downloadable at http://www.videolan.org/

- supports mostly ALL plattforms: Windows, Mac OS X, GNU/Linux, BeOS, Syllable, BSD, Solaris

It's necessary that you have administrator rights on your system (on linux plattforms it may differ). When using the K-Lite Codec Pack or the Free DivX software, you usually have to restart your system. The VLC media player plays immediately the videos after the installation process.

Linux

In order to playback the videos you need to have the codecs installed. Most distributions provide a codec package, sometimes called win32codecs. If you install them xine and mplayer can play the files. If you cannot find them go to the mplayer download page and download a Binary Codec package. If you have no root permissions you can store the codecs in ~/.mplayer/codecs.

Good luck!